Thu 15 Sep

16:50

Summacumfemmer, Leipzig

Constructive Trojans

Constructive disobedience has to overcome innumerable tricky situations in the building process. In Germany, the most sensitive point probably lies somewhere between Work Phase 5 (final planning) and the early stages of Work Phase 8 (in this case building supervision) – i.e. in the transition between the drawn and planned modelling of an idea and its architectural manifestation. At this point the array of project participants expands considerably, and disobedience has to assert itself against an ever-greater number of contradictory voices – faced with contractors, sub-contractors and site managers, as well as technical rules and norms. Whoever seeks to transcend conventions in the midst of this written and spoken static needs the appropriate communication tools. Architectural mock-ups can be these tools. Although, as a rule, they are seen as belonging to the earlier and freer design stages, by virtue of their un-scaled, life-sized nature, mock-ups nevertheless have the ability to partly create architectural reality [see Geiser 2021, 69]. Having said this, the architectural (near-) reality of the mock-up already enforces built facts, which are less contestable than prior drawn propositions. In this sense, mock-ups can make things more plausible, more convincing, but also more persuasive.

Normally mock-ups appear at prior determined moments when the process participants want to reassure themselves. The client wants to have another precautionary impression of what the built reality will look like (in the most extreme case as a 1:1 mock-up of the entire building, as for example with Peter Behrens and Mies van der Rohe’s designs for the Kröller-Müller House) [see Eidenbenz 2021, 15–16]. Or, alternatively, the architects want to convince themselves about the quality of the implementation work or the details where building specialities overlap (as with almost all facade mock-ups for larger developments).

The opposite of this is the disobedient mock-up, produced by the wrong professionals at the wrong time using wrong means. For example, the mock-up of a “winter garden” facade for the San Riemo housing cooperative building in Munich. Instead of being built by a contractor, we as architects erected it. This happened before the contract was awarded, not afterwards. The method was also flawed, because instead of using steel we applied MDF – albeit with the appearance of steel. Even more mistaken was the financing, in that we as architects considered the mock-up to be a present from us for the project. Nonetheless, everything that was ostensibly wrong (and disobedient) helped to overcome the critical barrier between the envisioned and the realised idea – making it logical in that sense. The disobedience of the planned construction itself required continual persuasive efforts on our part, which through conventional planning methods – such as drawings, performance specifications or even scaled models – would have fallen on deaf ears. Only the mock-up proved to speak a language that all of the participants could clearly hear, at the same time with a rhetoric that was convincing enough to generate understanding and plausibility. The mock-up triggered a communicative process during which the disobedient characteristic took at increasingly back seat and was superseded by a lucidity about the common goals.

These sorts of mock-ups are tools of self-empowerment. They are constructive Trojan Horses, which insinuate themselves subversively into the building process: not with the aim of ruining it, but in terms of a productive creative urge. Anyone can build them (or have them built): clients, contractors, officials – or indeed us architects too. If constructive disobedience means risking experimentation and all the while kicking ourselves about how beholden we are to the mainstream establishment, then we can simply get up from our desks and build ourselves. Happily mock-ups are not that large after all!

References

See Michael Eidenbenz, Lloyd’s 1:1 – The Currency of the Architectural Mock-Up (Zurich: gta Verlag, 2021).

Reto Geiser, ‘Between Representation and Reality’, in Reto Geiser (ed.), Archetypes: David K. Ross (Zurich: Park Books, 2021), 69–81.

mock-up of a “winter garden” facade for the San Riemo housing cooperative building in Munich

©SUMMACUMFEMMER

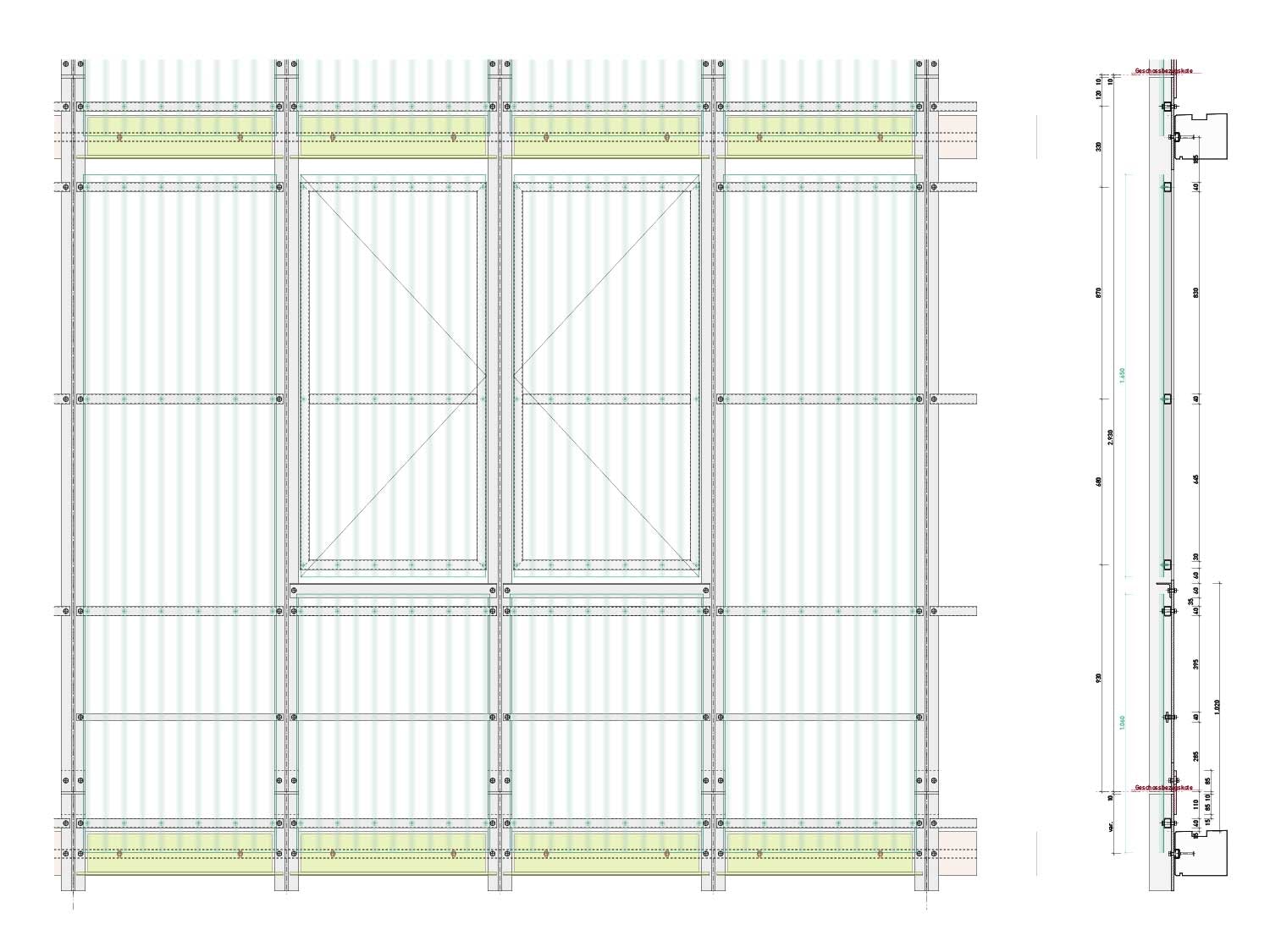

plan detail, “winter garden” facade for the San Riemo housing cooperative building in Munich

©SUMMACUMFEMMER

Anne Femmer

Anne Femmer (b.1984) is an architect and currently a visiting professor at TU Graz. Following her studies, she worked, amongst others, with Ballmoos Krucker Architekten and architecten de vylder vinck taillieu. In 2015 she founded the office SUMMACUMFEMMER Architekt*innen in Leipzig, together with Florian Summa. Parallel to her architectural work, she served as a design assistant for the chair of Christian Kerez and Jan de Vylder at ETH Zurich from 2015 to 2018. In 2020 she and Florian Summa taught a guest studio at the TU Munich. From 2020 to 2022 she supervised the Professorship in Integral Architecture at the TU Graz.

Florian Summa

Florian Summa (b.1982) is an architect and currently a visiting professor at the TU Graz. Following his studies he spent five years working for Caruso St John Architects in London and Zurich, and in 2015 founded the office SUMMACUMFEMMER Architekt*innen in Leipzig, together with Anne Femmer. Parallel to his architectural work, he served as a design assistant for the chair of Adam Caruso at ETH Zurich from 2015 to 2018. In 2020 he and Anne Femmer taught a guest studio at the TU Munich. From 2020 to 2022 he supervised the Professorship in Integral Architecture at the TU Graz.